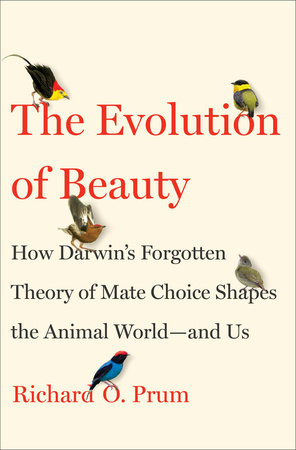

by Richard O. Prum

Whenever we wish to answer any question about the natural world, and we're in doubt about it, we usually turn to Darwin. Except, that is, when it comes to the question of beauty and how it exists in the world, according to Yale professor Richard Prum. The rejection of Darwin's ideas about sexual selection--as opposed to his theory of natural selection--by the bulk of evolutionary scientists serves as the inspiration for Prum's The Evolution of Beauty, a book written as a methodical (and methodological) counterpoint to the field's slavish devotion to adaptation as the answer to everything.

Prum makes it clear that he does not wish to reject the notion of adaptive mate choice--the evolutionary mechanism that is scientists' preferred answer for why animals evolve in every given way--but simply wishes to reassert an arbitrary character to certain processes that lead to many of the extraordinary forms and behaviors displayed by animals and humans.

|

| The Evolution of Beauty by Richard O. Prum |

Thus, if you're the type who likes to spend weekends hanging out at the Creationist Museum, this book is probably not for you.

If, however, you have an open mind--especially a mind more open than most of today's current crop of evolutionary scientists, according to Prum--then you're likely to profit from reading The Evolution of Beauty, particularly if you have long pondered the signficance of the differences we see among creatures in the world around us--including the creatures we see at the mall, the grocery store, and the office.

Frankly, the idea that much of the organic world's existence is governed by a notion of aesthetic mate choice--that is, mates are chosen not simply for their Darwinian "fitness," but also for how aesthetically pleasing they are to other members of their species--seems like something fairly obvious. This observer has long understood (to his own personal detriment) how "the birds with the brightest plumage are the ones who get the mates." It seems like a strain to deny that being beautiful works heavily to a creature's advantage, be that creature a Great Argus pheasant, a breed of dog, or a USC cheerleader.

Yet, according to Prum, that has largely been the case within the field of evolutionary science, where the out-sized influence of Alfred Russell Wallace (the co-discoverer with Darwin of natural selection) has worked for over a hundred years to champion the primacy of all-powerful adaptation as the cause of all evolutionary change.

As Prum establishes in his book's early chapters, the turn away from Darwin's theory of aesthetic mate choice as a key component of sexual selection was largely driven by Wallace's personal animus, along with hearty doses of Victorian-era primness, particularly with regards to female sexual autonomy. The implications of "this aesthetic view of life"--as Prum puts it, echoing Darwin's famous closing to Origin of Species--were a little too risque if not revolutionary for the staid world in which the famous naturalist first proposed them, and biological sciences clung to adaptation as a shield against any nervous-making ideas interfering with their solidly orderly and reasonable view of how animals evolve.

But now, in the 21st century--where primness is an idea that has dissolved and the culture has moved well beyond the boundary of quaintness--along comes Prum, an ornithologist who has taken a lifetime of observing birds and their mating rituals and identified behaviors and physical characteristics that simply can't be explained by mere adaptation, or "honest advertising" of physical superiority, as the adaptationist creed would have you believe.

Thus, most of the first half of The Evolution of Beauty presents Prum's examples from the field, where his observations--literally, his bird-watching excursions--of Great Argus pheasants, various species of Manakins and Bowerbirds, and other exotic avians introduced him to behaviors and traits that defy classification as advertisements of an individual bird's fitness. Prum explains how, in most of the species studied, female mate choice served as the engine for creating adjustments to the males who were seeking mates, either through changes in appearance or in behavior, that are not only not adaptive in nature, but in some instances can be considered maladaptive, at least from an individual's point of view. (The mating displays of male Manakins--where multiple males show coordinated behaviors that assure certain birds lose out on breeding opportunities--are particularly effective evidence.) The chapter on duck sex presents a surprisingly dramatic scenario that makes a sound case for just how strong--and urgent--is the female drive to adapt in order to preserve their sexual freedom--a freedom of choice that insists upon being able to preserve a hen's desire to mate with the drake who is most appealing to her.

Later in the book, Prum tackles how aesthetic mate choice works in the human species, from our divergence with our ape cousins all the way through to the rise of homosexuality as an open human sexual phenomenon in these later days (at least as a question of sexual identity, if not the more ancient mechanics of the thing). Subjects tackled in these later chapters are as colorful as the human male's lack of a baculum (penis bone) and the utility of female orgasms (maybe there isn't any, besides the fact that it feels good) to the sobering reality that many of the by-products of human aesthetic mate choice (by women) serve the purpose of nullifying "traditions" of sexual coercion and violence. It's a rich tapestry for sure, and bound to be of interest to anyone with an interest in human sexual dynamics--which is to say, everyone.

Prum's treatment of his subject is scholarly, but that doesn't mean it's too opaque for the average reader to comprehend. The professor doesn't dumb things down; he keeps his reporting as straightforward and clear as possible to serve the purpose of reaching, and influencing, a broad audience. So, too, does his writing style; Prum injects a healthy amount of humor and even pop culture references into his text, which certainly helps to lubricate the nonscientist's understanding of the subjects being discussed. For a work as intelligent and dense as The Evolution of Beauty, the book is in fact a relatively easy and enjoyable read. The author's only real misstep comes in his closing chapter, where he presents as a thematic anchor a gross misinterpretation of an old Greek aphorism, which then serves to undermine his closing argument. Other than that one fault, Prum's presentation is lucid, well-argued, and hard to refute.

So, then, does The Evolution of Beauty triumph in beating back the adaptationists' claims to universality? Yes, I think so, at least as far as the notion of the ubiquitous and unchangeable power of adaptive mate choice is concerned. There's too much here that argues too strongly in favor of that "aesthetic view of life" for all the eggs to be placed in the adaptive basket. But some of Prum's conclusions--"intellectual offerings" may be a more accurate description--remain highly speculative and are (by the author's own admission) still wanting in evidence to be claimed as fact. Overall, the case for aesthetic mate choice is strong, but, as the Scots might say, "not proven."

Still, The Evolution of Beauty is a welcome addition to the scientific bookshelf. Science only progresses--indeed, only happens--when questions are asked, particularly questions that challenge entrenched dogmas. Prum had done more than enough with this volume to raise important questions and set the course for the next generation of evolutionary biologists to find the proof for these ideas.

No comments:

Post a Comment